Author: Ronen Shekel

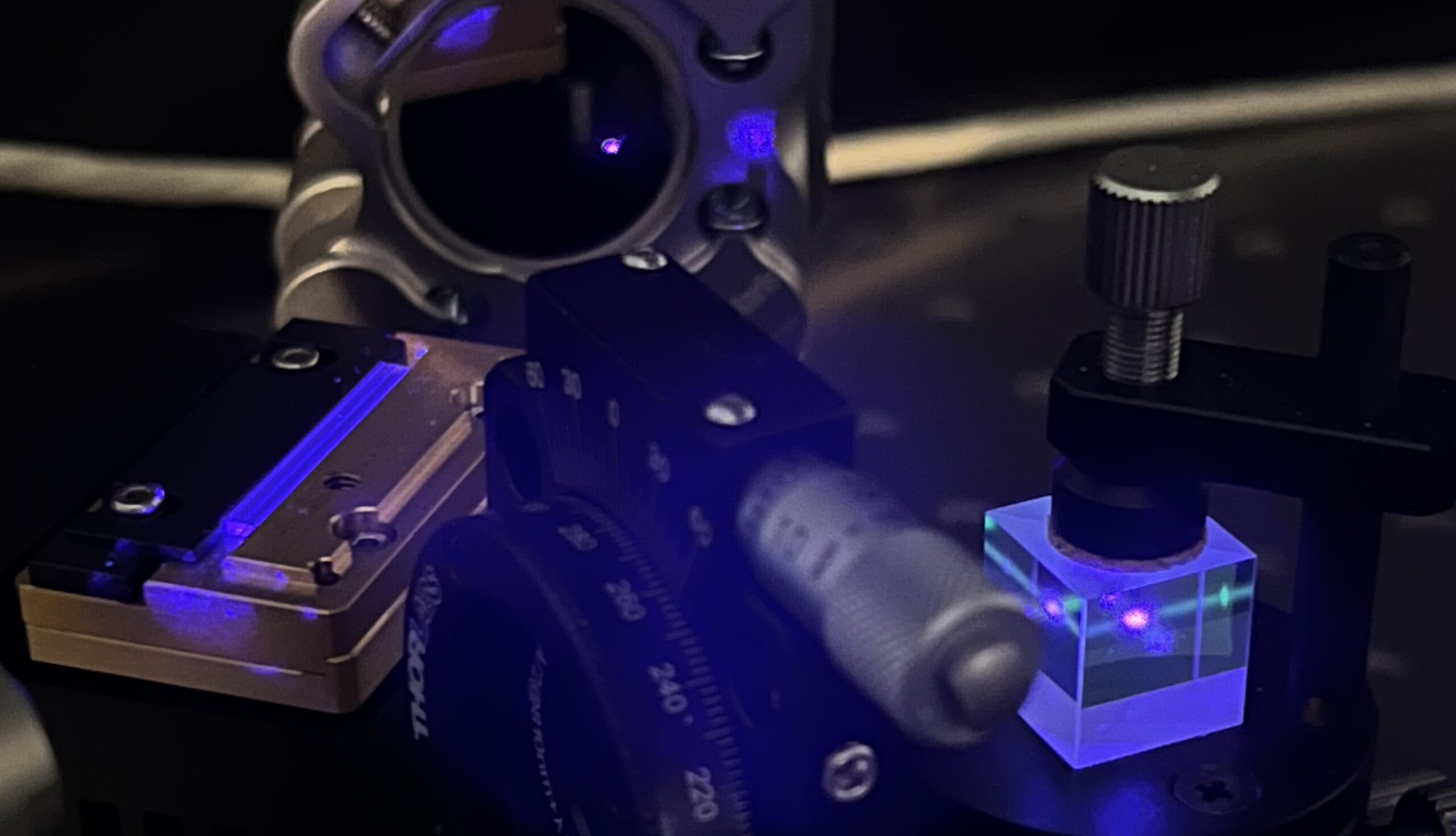

Spontaneous parametric down-conversion (SPDC) is a cornerstone of quantum optics, enabling the generation of entangled photon pairs with remarkable properties. One such property, dispersion cancellation, reveals how entanglement can mitigate effects that typically distort light as it travels through materials. This phenomenon, first explored in the early 1990s, offers both fundamental insights into quantum mechanics and practical applications in quantum technologies. In this post, we discuss how dispersion affects light, how entanglement counters it, and key experiments that have shaped our understanding.

Classical Dispersion: The Spreading of Light

When a short pulse of classical light travels through a vacuum, it retains its compact shape. However, propagation through a material like glass introduces a phenomenon known as dispersion. In a material, the refractive index varies with wavelength, n≈n0+β(λ-λ0 ), where β is the dispersion coefficient at a reference wavelength λ_0, causing different wavelengths of light to travel at different speeds. Since a short pulse comprises a range of wavelengths – owing to its Fourier composition – each component propagates at its own velocity. As a result, the pulse broadens over time.

In materials exhibiting normal dispersion, longer wavelengths (lower frequencies) tend to move faster, while in those with anomalous dispersion, shorter wavelengths (higher frequencies) take the lead. In either case, the outcome is the same: the initially sharp pulse spreads out, losing its compact temporal profile. This effect poses challenges for applications requiring precise timing or short pulses.

Franson’s Nonlocal Dispersion Cancellation

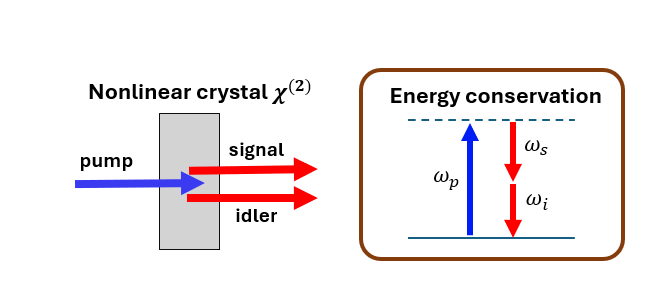

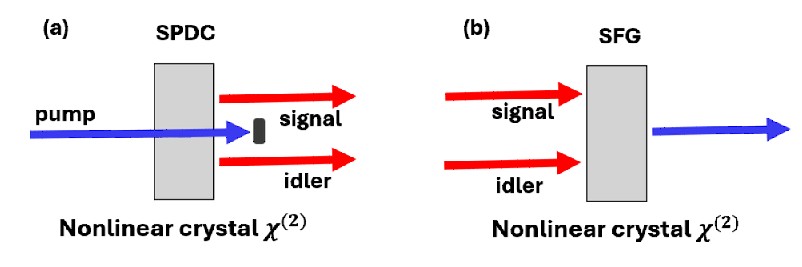

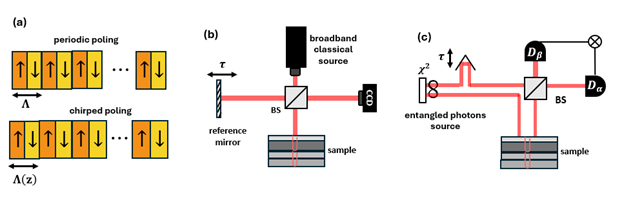

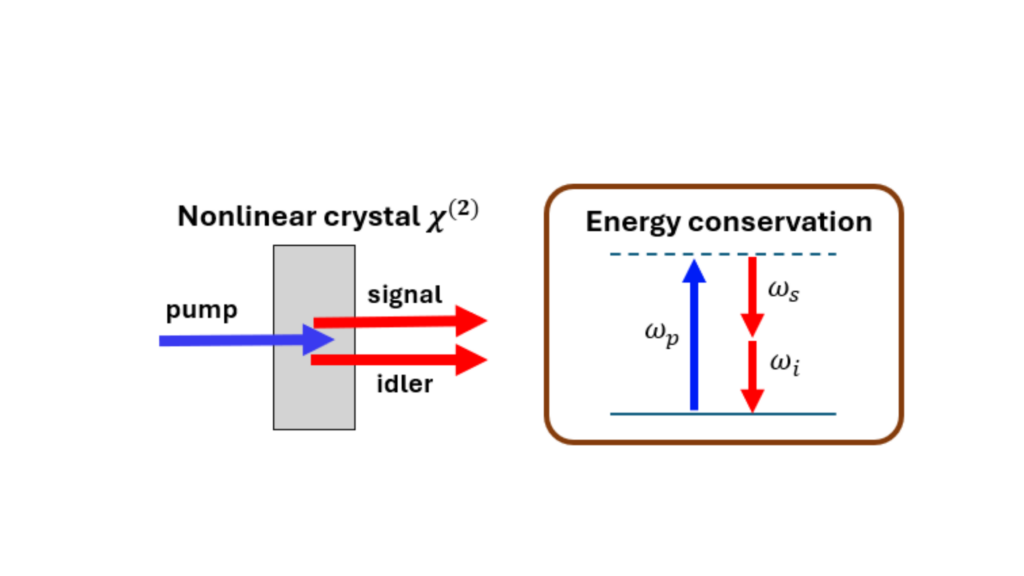

Consider now a pair of spectrally entangled photons generated via SPDC in a nonlinear crystal. A narrowband pump beam splits into two photons – signal and idler – whose frequencies are tightly correlated due to energy conservation (Fig. 1). When measured jointly, their arrival-time correlations are related to the temporal width of their wave-packets, set by their spectral bandwidth via the Fourier transform. But what happens when these photons travel through dispersive media, where dispersion smears each wave-packet and broadens their correlations?

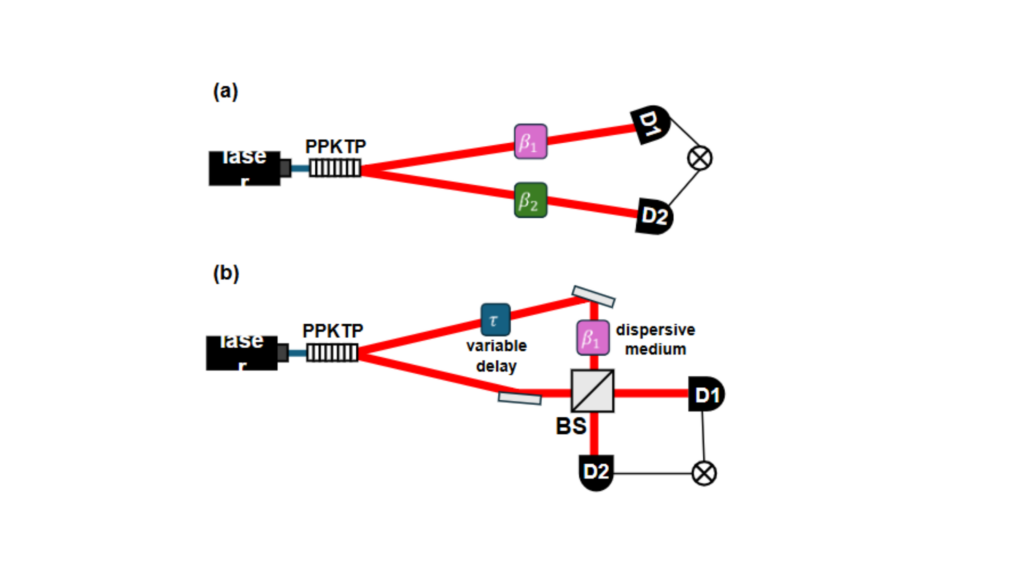

In 1992, J.D. Franson proposed an intriguing experiment (Fig. 2a). He suggested sending each photon through a different dispersive medium – one with normal dispersion, the other with anomalous dispersion – and then measuring their joint arrival times. Classically, one might expect the dispersion to broaden each photon’s wave-packet, resulting in a wider correlation profile. Surprisingly, Franson found that when the dispersions are opposite in sign, the broadening cancels out. The correlation remains as narrow as it was without dispersion!

This effect arises from the entangled nature of the photon pair. The joint two-photon state ensures that the dispersion experienced by one photon is precisely counteracted by that of its twin, a phenomenon described as nonlocal because the photons need not interact directly, and the two detectors might be very far away from each other. While classical analogs to this experiment exist [2], this cancellation highlights a distinctly quantum feature tied to entanglement, as the photons’ individual distortions are reconciled only through their shared state [3].

Steinberg’s Local Dispersion Cancellation

Shortly after Franson’s work, Aephraim Steinberg and colleagues proposed a complementary approach [4, 5]. In their experiment, only one of the entangled photons passes through a dispersive medium, while the other travels freely. The photons are then reunited at a beam splitter in a Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) interferometer (Fig. 2b), where identical photons exhibit a characteristic dip in coincidence counts due to destructive interference. Specifically, if two indistinguishable photons arrive at the beam splitter simultaneously, they will both exit in the same output port, thereby reducing coincidences and producing the HOM dip.

Once again, one might anticipate that dispersion would stretch the affected photon’s wave-packet, thereby reducing the overlap with its twin and broadening the HOM dip. However, Steinberg showed that the dip remains narrow, largely unaffected by the dispersion. This occurs because the two-photon amplitudes along possible paths through the beam splitter interfere in a way that cancels the dispersion’s impact. Remarkably, this setup also provided experimental evidence that a single photon travels through a material at its group velocity – the speed of the wave-packet’s peak – resolving a point of contention in photon propagation studies at the time.

Developments Since the 1990s

Since these pioneering experiments, dispersion cancellation has been explored in multiple contexts. The Franson effect has been demonstrated using diverse measurement methods [6, 7], and the dispersion cancellation concept has been extended to systems such as Mach-Zehnder interferometers [8] and optical cavities [9]. It has also been generalized to three-, or even multi-photon states [10], as well as to independent photons [11]. These advancements underscore the versatility of SPDC-generated photons and their utility in quantum optics research.

Implications and Applications

Dispersion cancellation illustrates how entanglement can preserve the integrity of quantum states against material-induced distortions. This property is valuable for quantum communication, where precise timing is critical, and for quantum imaging, where maintaining narrow correlations enhances resolution. At Raicol Crystals, we specialize in crafting nonlinear crystals that enable such experiments, providing researchers with the tools to explore and harness these effects. For more information on our quantum solutions, visit our quantum components page, or contact us directly.

References

[1] Franson, J. D. “Nonlocal cancellation of dispersion.” Physical Review A 45, no. 5 (1992): 3126.

[2] Shapiro, Jeffrey H. “Dispersion cancellation with phase-sensitive Gaussian-state light.” Physical Review A—Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics 81, no. 2 (2010): 023824.

[3] Franson, J. D. “Lack of dispersion cancellation with classical phase-sensitive light.” Physical Review A—Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics 81, no. 2 (2010): 023825.

[4] Steinberg, A. M., P. G. Kwiat, and R. Y. Chiao. “Dispersion cancellation in a measurement of the single-photon propagation velocity in glass.” Physical review letters 68, no. 16 (1992): 2421.

[5] Steinberg, Aephraim M., Paul G. Kwiat, and Raymond Y. Chiao. “Dispersion cancellation and high-resolution time measurements in a fourth-order optical interferometer.” Physical Review A 45, no. 9 (1992): 6659.

[6] Baek, So-Young, Young-Wook Cho, and Yoon-Ho Kim. “Nonlocal dispersion cancellation using entangled photons.” Optics express 17, no. 21 (2009): 19241-19252.

[7] O’Donnell, Kevin A. “Observations of dispersion cancellation of entangled photon pairs.” Physical review letters 106, no. 6 (2011): 063601.

[8] Larchuk, Todd S., Malvin C. Teich, and Bahaa EA Saleh. “Nonlocal cancellation of dispersive broadening in Mach-Zehnder interferometers.” Physical Review A 52, no. 5 (1995): 4145.

[9] Agarwal, Girish S., and S. Dutta Gupta. “Filtering of two-photon quantum correlations by optical cavities: Cancellation of dispersive effects.” Physical Review A 49, no. 5 (1994): 3954.

[10] Nodurft, I. C., S. U. Shringarpure, B. T. Kirby, T. B. Pittman, and J. D. Franson. “Nonlocal dispersion cancellation for three or more photons.” Physical Review A 102, no. 1 (2020): 013713.

[11] Im, Dong-Gil, Yosep Kim, and Yoon-Ho Kim. “Dispersion cancellation in a quantum interferometer with independent single photons.” Optics Express 29, no. 2 (2021): 2348-2363.