Author: Ronen Shekel

Medical imaging relentlessly pushes toward higher resolution. Distinguishing features separated by mere micrometers can mean the difference between early disease detection and a missed diagnosis. However, conventional optical coherence tomography (OCT), despite impressive resolution, faces a fundamental tradeoff: as bandwidth broadens to enhance resolution, dispersion in biological tissues increasingly smears the very features we seek to resolve.

Quantum optics offers a remarkable solution. By harnessing entangled photon pairs from specially engineered crystals, we can completely cancel the effect of sample dispersion and achieve twice the axial resolution of classical methods. The key enabler is chirped aperiodically poled KTP (APKTP), which generates the ultra-broadband entangled photons essential for this quantum sensing achievement.

Broadband biphoton generation

High temporal resolution requires a broad frequency spectrum – a fundamental Fourier relationship. For quantum technologies using photon pairs, this means generating photons entangled over vast frequency ranges.

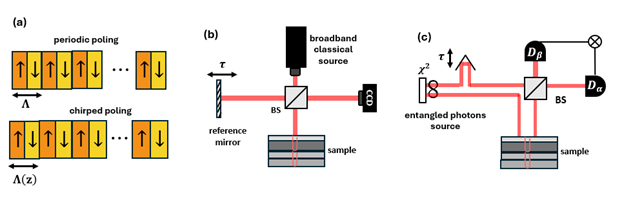

Standard periodically poled crystals (PPKTP) phase match only relatively narrow frequency bands. Chirped APKTP, however, gradually varies the poling period along the crystal length (Fig. 1a), phase-matching different frequencies at distinct positions along the crystal [1-3]. This seamlessly integrates multiple phase-matching conditions into a single crystal, enabling photon pairs to span ultrabroad spectra. Such chirped crystals have demonstrated a bandwidth of 300nm, with record-breaking Hong-Ou-Mandel (HOM) interference of <10 fs width [1], a hallmark of ultrashort temporal correlations [4]. This spectral engineering is invaluable also for advanced quantum imaging [5], spectroscopy [6] and tomography [7] applications.

A different method for broadband biphoton generation is utilizing a natural advantage of KTP: it has a zero group-velocity dispersion wavelength at approximately 1789 nm for light polarized along the crystallographic Z axis of KTP [8,9]. Near this “sweet spot,” the bandwidth of type-0 SPDC is limited only by higher-order dispersion, enabling biphoton spectral widths approaching 1000 nm even without chirped poling.

Classical and quantum OCT

Optical coherence tomography uses broadband light in a low-coherence interferometer to create cross-sectional images of subsurface structures. Light split between reference and sample arms (Fig. 1b) produces interference only when path lengths match within the source’s coherence length, enabling depth profiling with a precision resolution of a few μm in medical applications.

However, OCT faces a practical limitation: group velocity dispersion. Different wavelengths travel at different speeds through materials, smearing pulses and reducing resolution. Consequently, as bandwidth broadens to improve resolution, dispersion increasingly limits OCT’s performance.

Quantum Optical Coherence Tomography (QOCT), proposed in 2002 [10,11], utilizes spectrally entangled photon pairs where one photon probes the sample while its twin serves as a reference (Fig. 1c). This quantum approach provides two remarkable advantages. First, it inherently cancels sample dispersion effects through a local dispersion cancellation effect [12], which we discussed in a previous post. Second, QOCT delivers a factor-of-two improvement in axial resolution: Two-photon quantum interference depends on the paths travelled by both photons, doubling sensitivity to optical delays compared to classical methods.

Since 2002 many advancements have been made in the field of classical OCT, with new ideas such as spectral-domain OCT and swept-source OCT [13], as well as new quantum OCT configurations [7].

Combining LBO optical parametric amplifier with CPA – (OPCPA).

Over the last decade domain engineering has undergone significant development [14], and here at Raicol, we advance the available technology by producing advanced crystals like chirped APKTP to translate quantum concepts into reality. Our expertise in periodic and aperiodic poling allows custom crystals optimized for various quantum applications. Through collaborations like the European QuantERA project SPARQL, we’re committed to advancing quantum technologies. Contact us to discuss how our crystal engineering can empower your quantum research and products.

References

[1] Nasr, Magued B., Silvia Carrasco, Bahaa EA Saleh, Alexander V. Sergienko, Malvin C. Teich, Juan P. Torres, Lluis Torner, David S. Hum, and Martin M. Fejer. “Ultrabroadband biphotons generated via chirped quasi-phase-matched optical parametric down-conversion.” Physical review letters 100, no. 18 (2008): 183601.

[2] Brida, Giorgio, M. V. Chekhova, I. P. Degiovanni, M. Genovese, G. Kh Kitaeva, A. Meda, and O. A. Shumilkina. “Chirped biphotons and their compression in optical fibers.” Physical review letters 103, no. 19 (2009): 193602.

[3] Wang, Jinbao, and Haibo Lin. “The single-cycle biphotons generated by noncollinear SPDC in the chirped QPM crystals.” Journal of the European Optical Society-Rapid Publications 20, no. 1 (2024): 6.

[4] Hong, Chong-Ki, Zhe-Yu Ou, and Leonard Mandel. “Measurement of subpicosecond time intervals between two photons by interference.” Physical review letters 59, no. 18 (1987): 2044.

[5] Lemos, Gabriela Barreto, Victoria Borish, Garrett D. Cole, Sven Ramelow, Radek Lapkiewicz, and Anton Zeilinger. “Quantum imaging with undetected photons.” Nature 512, no. 7515 (2014): 409-412.

[6] Kalashnikov, Dmitry A., Anna V. Paterova, Sergei P. Kulik, and Leonid A. Krivitsky. “Infrared spectroscopy with visible light.” Nature Photonics 10, no. 2 (2016): 98-101.

[7] Vanselow, Aron, Paul Kaufmann, Ivan Zorin, Bettina Heise, Helen M. Chrzanowski, and Sven Ramelow. “Frequency-domain optical coherence tomography with undetected mid-infrared photons.” Optica 7, no. 12 (2020): 1729-1736.

[8] Viotti, Anne-Lise. Nonlinear optics in KTiOPO4 for spectral management of ultra-short pulses in the near-and mid-IR. Diss. KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2019.

[9] https://refractiveindex.info

[10] Abouraddy, Ayman F., Magued B. Nasr, Bahaa EA Saleh, Alexander V. Sergienko, and Malvin C. Teich. “Quantum-optical coherence tomography with dispersion cancellation.” Physical Review A 65, no. 5 (2002): 053817.

[11] Nasr, Magued B., Bahaa EA Saleh, Alexander V. Sergienko, and Malvin C. Teich. “Demonstration of dispersion-canceled quantum-optical coherence tomography.” Physical review letters 91, no. 8 (2003): 083601.

[12] Steinberg, Aephraim M., Paul G. Kwiat, and Raymond Y. Chiao. “Dispersion cancellation and high-resolution time measurements in a fourth-order optical interferometer.” Physical Review A 45, no. 9 (1992): 6659.

[13] Ge, Xin, Shufen Chen, Si Chen, and Linbo Liu. “High resolution optical coherence tomography.” Journal of Lightwave Technology 39, no. 12 (2021): 3824-3835.

[14] Weiss, Tim F., and Alberto Peruzzo. “Nonlinear domain engineering for quantum technologies.” Applied Physics Reviews 12, no. 1 (2025).

Do you have a question? Our experts will be happy to hear from you and advise you on the best product for you. Contact Us.

Have you already subscribed to our YouTube channel? Don’t miss out—subscribe now for exclusive content and updates from our company.

Author: Dr. Noa Voloch Bloch and Ori Levin

Raicol, a renowned leader in PPKTP manufacturing, is committed to propelling the quantum industry forward through state-of-the-art solutions. Over the past few years, our relentless pursuit of excellence has led to significant enhancements in our manufacturing capabilities. Notably, we have dedicated substantial efforts to refining our proficiency in producing shorter poling periods.

While achieving short poling periods for individual elements with low yields is indeed feasible, the real challenge lies in scaling this capability for mass production and making it accessible to our valued customers at a competitive price point. Our engineer, Mr. Michael Schindler, has achieved a breakthrough by developing a process that enables extremely short poling periods (a full cycle of approximately 1 µm). As a result, we are proud to offer a standard poling period of less than 3 µm.

At Raicol, we remain committed to pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in the quantum industry, and our dedication to innovation continues to drive our success.

Narrow bandwidth SPDC

Raicol recently experienced a significant increase in demand for PPKTP crystals with extremely short poling periods. This demand was primarily driven by applications in narrow-band “Counter Propagation SPDC,” which can achieve bandwidths as low as 0.06 nm [1,2]. The importance of these narrow bandwidths lies in their potential for integrating SPDC sources with quantum memories, where matching the bandwidths of atomic transitions and exciting radiation is crucial. The relationship between crystal length and SPDC bandwidth is inverse, with longer crystals producing narrower bandwidths. While Raicol continues to improve its capabilities in this area, the company currently offers PPKTP crystals up to 30 mm in length. This development demonstrates Raicol’s ongoing commitment to advancing quantum technologies and meeting the evolving needs of the photonics industry. As the field of quantum optics continues to progress, Raicol remains dedicated to exploring innovative solutions and pushing the boundaries of PPKTP crystal manufacturing. The company’s efforts in producing crystals with extremely short poling periods and longer lengths are contributing to the advancement of quantum memory integration and other cutting-edge applications in quantum technologies.

Production validation to short poling

As a leader in nonlinear crystal manufacturing we maintain rigorous quality control procedures, especially when developing new crystals or cutting-edge technologies. When trying to implement short poling we faced challenge in characterizing and validating short-polled KTP crystals. While Raicol’s measuring testing systems are typically designed for forward-propagating Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) and Spontaneous Parametric Down-Conversion (SPDC) across various wavelengths. However, the short-period polled KTP crystals presented a distinct obstacle. The absence of forward SHG/SPDC processes corresponding to the short period, due to their occurrence near the edge of the KTP transmission window, made conventional collinear second harmonic processes unsuitable for evaluation of 1.2 µm polled crystals. This situation underscores the complexity of validating advanced crystal technologies and highlights Raicol’s commitment to ensuring product performance through innovative testing methodologies.

A. Backward second harmonic generation

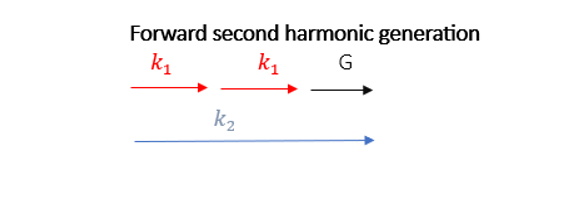

There are two distinct types of collinear second harmonic generation SHG processes [3]: forward and backward propagation:

Forward Second Harmonic Generation: In this process, the beam at the doubled frequency propagates in the same direction as the beam at the fundamental frequency. In the case of PPKTP the shortest poling period enabling efficient frequency doubling from 800 nm pump to 400 nm is approximately 3 µm.

Backward Second Harmonic Generation: In this process, the generated wave propagates in the opposite direction of the pump.

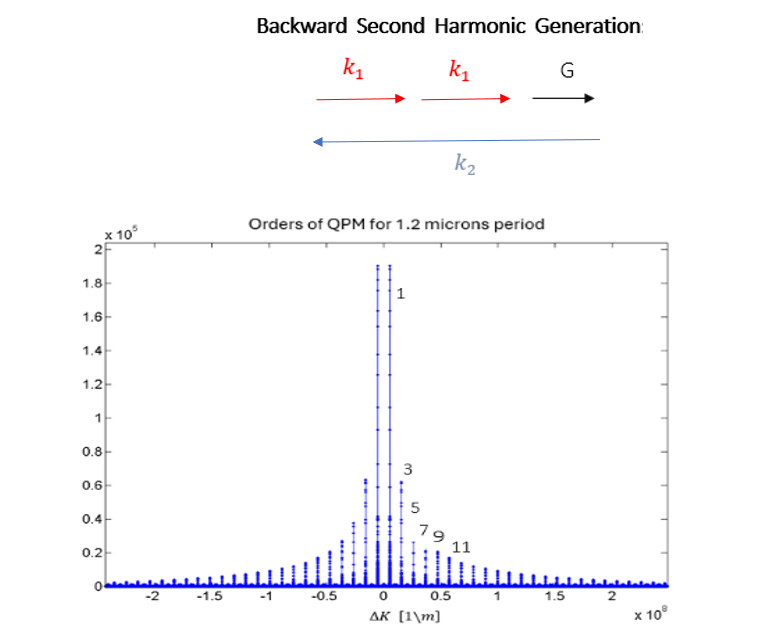

However, the periods necessary for efficient backward second harmonic generation for visible wavelengths are extremely short and pose significant manufacturing challenges. For example, generating a second harmonic of 829 nm light in the first-order QPM requires a period of 0.109 µm.

B. Backward propagation test bench

In order to characterize our 1.2 short poling crystals we measure SH backward propagation, we evaluated the ΔK that matches the phase matching values of 1.2 µm grating periods. For the ΔK values shown in the graph there is no forward process. But for the 829 nm converted to 414.4 nm at 33 deg PPKTP

The ΔK is 5.754⋅10^7 [1/m] specifically suites phase matching of the 11-th order shown in the graph. Backward second harmonic generation of 829 nm converted to 414.5nm [3].

To overcome this challenge, we implement a backward propagation test system, as outlined below: The 829 nm pump beam enters the crystal and the SH which propagates backward is deflected by a dichroic mirror to the detector.

[1] Liu, YC., Guo, DJ., Ren, KQ. et al. Observation of frequency-uncorrelated photon pairs generated by counter-propagating spontaneous parametric down-conversion. Sci Rep 11, 12628 (2021).

[2] Zhang, H., Jin, XM., Yang, J. et al. Preparation and storage of frequency-uncorrelated entangled photons from cavity-enhanced spontaneous parametric downconversion. Nature Photon 5, 628–632 (2011).

[3] S. Moscovich, A. Arie, R. Urenski, A. Agronin, G. Rosenman and T. Rosenwaks, “Noncollinear second harmonic generation in sub-micrometer poled RbTiOPO4”, Optics Express, 12, 2236-2242 (2004).

Do you have a question? Our experts will be happy to hear from you and advise you on the best product for you. Contact Us.

Have you already subscribed to our YouTube channel? Don’t miss out—subscribe now for exclusive content and updates from our company.

Author: Ronen Shekel

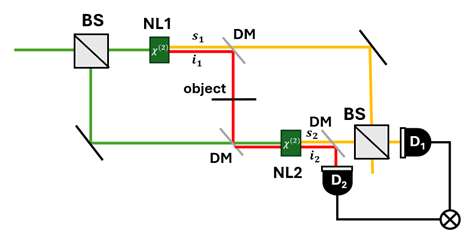

One of the most beautiful experiments with SPDC light is that of induced coherence. It has originally been demonstrated and analyzed by Zou, Wang, and Mandel in 1991 [1, 2], and is discussed and utilized to this day. In this experiment two nonlinear crystals are used, set in a configuration as shown in Fig. 1.

A “green” pump beam generates via parametric down conversion “yellow” signal and “red” idler photons, both in the first crystal and in the second crystal. We then slightly change the length difference between the paths of the two yellow signal photons and measure their interference using a single photon detector (D1). The question arises – will we measure interference fringes? Are these signals coherent with each other?

Well, since we cannot know which of the two signal photons we are measuring, we should indeed sum the amplitudes, and do observe interference. However, consider now a case where we block the path of the first idler photon (). Remarkably, even though signal photons can still originate from either the first or the second crystal, the fringes will disappear!

This may again be explained in terms of distinguishability. In Feynman’s words [3]:

If you cannot distinguish the final states even in principle, then the probability amplitudes must be summed.

Further examination of our system shows that blocking the first idler photon does affect the distinguishability between the two signal photons. If the signal photon is accompanied by an idler photon at the second detector (D2) then we know that it originates from the second crystal. If we don’t measure an idler photon – we know that it has been blocked, and that the signal photon originates from the first crystal. Thus, blocking the first idler photon reduces the indistinguishability between the two signal photons.

This is quite remarkable. Even when both processes have a low flux, and statistically, in no point in time the first idler and the second signal photon co-exist, the mere theoretical possibility of measuring the idler photon from the first crystal affects the coherence properties of the signal photon generated in the second crystal. For this reason, we say that the idler photon induces the coherence of the process.

In 2014, this effect has been utilized in the group of Nobel prize winner Anton Zeilinger, in the context of imaging [4]. Consider that we block only part of the path of this idler photon and swap the single photon detector with a sensitive camera. The area on the camera corresponding to the blocked area will show no interference, while the other area will show interference.

Measuring intensity that depends on the transmittance of an object is of course exactly what we want to do in imaging! Notice however the puzzling fact: the light measured by the camera never passed through the object, and the light hitting the object never reaches the camera!

A second modality for using induced coherence for imaging is for phase imaging: the phase accumulated by the idler photon is simply transferred to the signal photon. Such a modality provides interesting configurations such as where the light hitting the object is at a wavelength not detectable by the used camera. Alternatively, it also works when the object is completely transparent or even completely opaque in the wavelength detected by the camera.

While this imaging technique is no doubt intriguing, providing materials for many new experiments conducted to this day [5], the exact quantum nature of the method has been debated. Indeed, in [6] it has shown that virtually all the features of the experiment can be realized in a quantum-mimetic fashion using classical light. The discussion has since continued, for example in [7] and [8].

In various undetected photon experiments different nonlinear crystals have been used, such as BBO or PPKTP, but in principle almost any nonlinear process could produce similar results [4]. If you want to join the discussion, get your own crystals at Raicol, where we provide the best world-class nonlinear crystals and find your own novel imaging modality!

[1] Zou, X. Y., Lei J. Wang, and Leonard Mandel. “Induced coherence and indistinguishability in optical interference.” Physical review letters 67, no. 3 (1991): 318.

[2] Wang, L. J., X. Y. Zou, and L. Mandel. “Induced coherence without induced emission.” Physical Review A 44, no. 7 (1991): 4614.

[3] Feynman, Richard P. (Richard Phillips), 1918-1988. The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Reading, Mass. :Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 19631965. Vol. III, chapter 03, “Probability Amplitudes”.

[4] Lemos, Gabriela Barreto, Victoria Borish, Garrett D. Cole, Sven Ramelow, Radek Lapkiewicz, and Anton Zeilinger. “Quantum imaging with undetected photons.” Nature 512, no. 7515 (2014): 409-412.

[5] Pearce, Emma, Osian Wolley, Simon P. Mekhail, Thomas Gregory, Nathan R. Gemmell, Rupert F. Oulton, Alex S. Clark, Chris C. Phillips, and Miles J. Padgett. “Single-frame transmission and phase imaging using off-axis holography with undetected photons.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.13389 (2024).

[6] Shapiro, Jeffrey H., Dheera Venkatraman, and Franco NC Wong. “Classical imaging with undetected photons.” Scientific Reports 5, no. 1 (2015): 10329.

[7] Kolobov, Mikhail I., Enno Giese, Samuel Lemieux, Robert Fickler, and Robert W. Boyd. “Controlling induced coherence for quantum imaging.” Journal of Optics 19, no. 5 (2017): 054003.

[8] Lahiri, Mayukh, Armin Hochrainer, Radek Lapkiewicz, Gabriela Barreto Lemos, and Anton Zeilinger. “Nonclassicality of induced coherence without induced emission.” Physical Review A 100, no. 5 (2019): 053839.

Do you have a question? Our experts will be happy to hear from you and advise you on the best product for you. Contact Us.

Have you already subscribed to our YouTube channel? Don’t miss out—subscribe now for exclusive content and updates from our company.

Author: Dr. Noa Bloch

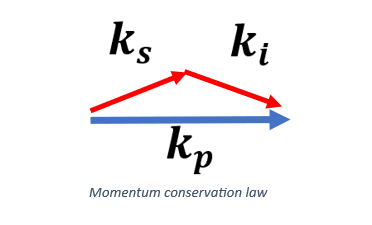

In nonlinear crystals, a special nonlinear process occurs. A pump photon is spontaneously converted into two complementary photons with lower energy. In this process both energy and momentum are conserved, i.e. and .

In PPKTP Crystal or APKTP Crystal the momentum mismatch of the process is compensated by the crystal reciprocal vector which is determined by the spatial frequency .

Vacuum energy and momentum fluctuations give rise to the spontaneous creation and annihilation of many random photons.

But the output photons of the SPDC (spontaneous parametric down-conversion nonlinear process) are the ones that conserve momentum and energy.

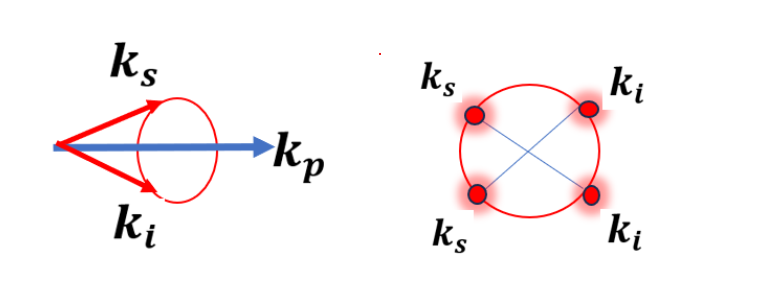

In type 1 SPDC all the photon pairs which conserve momentum are positioned on a ring shaped structure:

In type 1 SPDC all the photon pairs which conserve momentum are positioned on a ring shaped structure:

See a movie

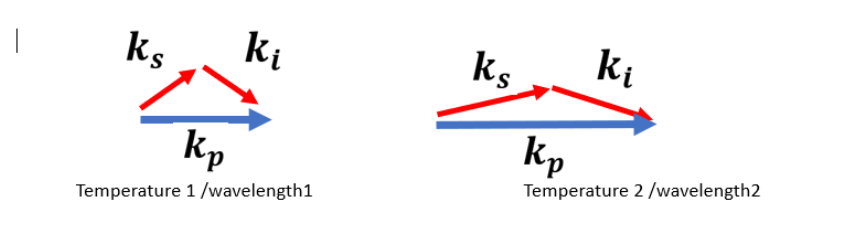

Changing the temperature or wavelength of the crystal will change the phase matching condition thus radius of the rings will be changed as well as seen in the movie.

Do you have a question? Our experts will be happy to hear from you and advise you on the best product for you. Contact Us.

Have you already subscribed to our YouTube channel? Don’t miss out—subscribe now for exclusive content and updates from our company

A growing number of companies are switching to industrial RTP crystals for electro-optic Pockels cells

In the past year, there has been a growing trend for industrial companies to switch their traditional Pockels cell (PC) components, mostly KD*P, to industrial RTP Crystal.

The excellent EO properties of RTP, its simple setup and configuration, along with its attractive pricing, makes it a great alternative for current PC solutions. Industrial RTP enables increased ROI for a project, by saving time and money for the laser production line and across the product’s lifetime.

About RTP

RTP belongs to the KTP Crystal family. The outstanding electro-optical properties of RTP, together with its high damage threshold, enable its use in high-end laser applications, it is ideal for use in applications that require advanced characteristics, such as being non-hygroscopic, having high thermal stability, and for higher-repetition rates.

Raicol’s RTP PC is widely recognized for the following features:

- Higher laser damage threshold

- Non-hygroscopic material

- Low absorption losses

- No acoustic ringing (up to at least 200kHz)

- Stability over a wide temperature range (10ºC –50ºC)

While providing many advantages over existing solutions, the advanced properties of RTP came with a price tag that prevented its widespread use for industrial applications.

Raicol’s new industrial RTP

Raicol’s new iRTP PC is the first product that brings the advantages of RTP to the EO mass market. The modified iRTP PC version of Raicol’s RTP is especially designed for the needs of the industrial laser market. Raicol’s iRTP PC is a standard off-the-shelf RTP PC that offers high performance EO cells at the price level of standard industry PCs.

iRTP vs KD*P Benefits

- Improved thermal stability – iRTP has thermal stability over a wide range of temperatures, eliminating the need for thermal stabilization, thus eliminating the need for an oven or thermal control systems.

- Reduce laser initiation time – RTP’s high thermal stability reduces laser stabilization and start up times, as well as the overall system initiation time.

- Simple alignment – iRTP requires only 1D alignment to reach an optimum extinction ratio, in comparison to KD*P, which requires 3D axis control-significantly complexifying the alignment process.

- Environmental stability- iRTP is a non-hygroscopic material with a temperature compensation design that allows it to function in non-controlled environments with a variety of temperatures and humidity levels.

- Mechanical robustness and stability – iRTP’s requirement for only 1D alignment means that the iRTP package and mount has a simple and more mechanically stable design. The working parameters do not change throughout the laser’s lifetime, or during temperature changes, hence, requires little to no calibration over time.

- Small size – The size and footprint of iRTP is much smaller compared to similar KD*P, due to a reduction in assembly, alignment, and temperature control components.

- High repetition rate – iRTP supports a repetition rate up to 200 kHz.

- Standard Pockels cell assembly – iRTP is an off-the-shelf product with standard industry EO cell specifications.

- High damage threshold – iRTPs high damage threshold enables its use for high power lasers.

Do you have a question? Our experts will be happy to hear from you and advise you on the best product for you. Contact Us.

Have you already subscribed to our YouTube channel? Don’t miss out—subscribe now for exclusive content and updates from our company.